Integrating Policy with Technology: How an experimental tech team redefines the way we think about problem-solving

Years ago, as a younger officer who had just joined the Singapore public service, I sat in a classroom listening to a senior civil servant share his philosophy for policy making. “Policy is implementation.” He said, “what’s on paper is only as good as what is actually practiced on the ground.” It sounded like good advice; I scribbled it in my notebook at the time and kept it at the back of my mind.

Six years later, as a policymaker turned product manager in the government who has had more practice in real-world implementation of policies, I found myself revisiting his piece of advice. I walked down the memory lane of having been part of different ministries within the Singapore government and being part of COVID-19 operations that supported the country’s transition from pandemic to endemic, more than two years since Singapore reported its first COVID case. It was not unusual to hear fellow public servants recollecting that “we were building planes while flying it” – policies were being made in quick succession, often evolving within days or weeks of its introduction.

Amidst the pandemic, some policies – such as wage support – had been generally welcomed, while others – such as dine-out policies in their myriad permutations – were met with some initial confusion. At the height of the pandemic, government hotlines around the world (if they were in place) had been ringing non-stop as people struggled to understand the latest policies that governed every facet of their lives, from isolation to travel protocols, from family visits, gatherings, and whether they could dine out.

Implementation is Policy

It seemed timely to update his piece of advice. If there was anything I had learned in the past few years working in public service and witnessing how policy, operations, technology, and communications came together, it was this: Policy is implementation. Implementation is policy. It’s not only that policy comes alive through the implementation of it, it’s that effective policymaking happens through it. Through real-world implementation, we discover bounds and constraints, as well as options and possibilities in a given problem space.

When the team I work with at Open Government Products took on the mission to roll out the COVID-19 vaccine, a few uncertainties initially gave us pause. In the early days of the programme, vaccine hesitancy had made it challenging for governments around the world to maximise immunisation coverage for the whole population. To minimise wastage of vaccine doses and ensure that the most vulnerable populations were given priority access, we needed to release vaccine supply to the desired population segments in a targeted and timely way. There was also a need to avoid long lines at vaccine centres, lest they become hotspots for the very virus it was intended to curb.

To gauge the addressable market accurately, the team decided to implement a pre-registration workflow that invited people to register their interest for vaccination in advance. Within a matter of hours, the product team had prototyped a form integrated with a messaging protocol that would send personalised SMS notifications for online booking to specific population groups. We co-created the policy for pre-registration and gradual release of vaccine supply for identified groups and built systems that could release appointment slots in a flexible way amidst supply uncertainty. When it was unclear if seniors were digitally savvy enough to access online appointments, we built a prototype of a simple, easy-to-use appointment system and tested it with seniors at neighbourhood community centres before launching it to the country. It turned out that seniors were more digitally savvy than we initially thought: more than 50% of them had booked their appointments online, mostly unassisted. This observation invited policymakers and operational staff to rethink our strategies for getting seniors vaccinated.

The view that “implementation is policy” is not about whether one is more important than the other; in reality both are two sides of the same coin. The making of policy happens through the process of implementation, not in advance of it. By prototyping or trying something out in the wild, we can discover or redefine the shape of the problem and challenge our own biases and assumptions – whether this is about expected user behaviour or incentive structures that undergird our systems. We can begin to ‘get it wrong to get it right’, to fail fast and fail cheaply to avoid potentially expensive errors that compound with any large-scale rollouts.

How can governments organise themselves to implement policies at speed, when there is no reliable playbook for what works? There are two things my team and I at Open Government Products have found helpful: getting better at collective improvisation (what I’d loosely call ‘playing jazz’) and closing the feedback loop through real-world metrics.

Playing jazz: policy implementation as collective improvisation

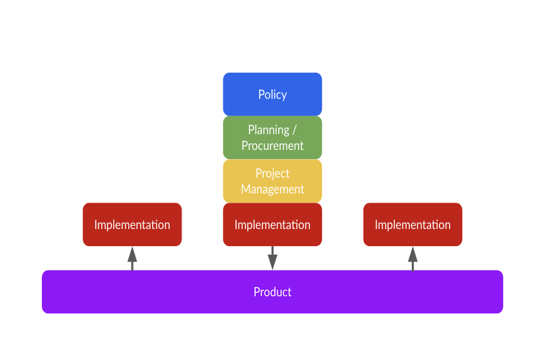

In a fast-paced and volatile environment, we can hardly afford to wait months or years for policies to be properly drafted, deliberated, inked, approved, only to realise that the operating context has shifted and the ‘approved’ course of action is no longer fit for purpose. To accelerate collective improvisation, we form Vertically Integrated Policy Teams (VIPTs) that bring public officers out of traditional vertical silos to form integrated teams with representation from across policy, operations, technology, communications, and specialist domains (e.g., clinicians). In this construct, cross-functional teamwork is the norm rather than the exception, and officers assume open-ended ownership of the problem, guided but not limited by their role or function.

The goal is to achieve a ‘more perfect union’ between the teams that formulate policies and teams who implement them. In a VIPT, operational staff do not take a policy as a given; there is room for understanding and questioning a given policy intent, with the aim of sharpening it or reshaping it to reflect ground realities more accurately. In an anti-scam VIPT, for example, technologists have been able to shape policies and operations around scam reporting and blocking by bringing about new operational possibilities through technology. Amidst Covid-19, VIPTs also created room for ground operational staff to shape product visions behind the suite of Covid-19 technology applications, which in turn influenced policies around vaccination, testing, travel, and safe re-opening of the country.

Having public officers across functions work in integrated teams also builds stronger relational trust, creating safer spaces for teams to acknowledge where they may have erred, enabling us to minimise blindspots, course-correct where necessary, and achieve better outcomes collectively. Like jazz, collective improvisation in policy implementation is an adaptive process: how we recover from ‘wrong notes’ matters more than getting it perfectly right the first time.

Closing the feedback loop

What unites officers coming from different backgrounds and functions is the pragmatic pursuit of ‘what works’, which is critically informed by a closed feedback loop that measures what matters (for the mission, and the people we serve). Creating closed feedback loops demand clarity around three things: 1) what good looks like, 2) what the team is setting out to achieve, and 3) metrics that track outcomes.

Knowing what good looks like helps a team locate the true north of a mission, which helps to define a realistic course of action. Metrics closes the feedback loop and tells us not only if we have succeeded, but also when we have erred or fallen short. Singapore’s vaccine rollout would not have been a success if we did not have the near real-time data on the number of people who had completed their doses, and their demographic, to inform policy and operational decisions at each phase of the programme. Anti-scam measures could not be said to work until a visible decrease in the number of individuals affected by scammers is observed, and financial losses are significantly reduced. Whether it is quantitative data or qualitative surveys, real-world metrics help to keep us attuned to the outcomes we set out to achieve, like a tuner that tells us when we have gone off-key.

At its heart, integrating policy and implementation is about focusing on impact rather than input. The difference between ‘technically done’ and ‘done’ lies in the relentless pursuit of a good idea well implemented over a great idea that is poorly implemented. There have been philosophical debates that create false dichotomies between ‘policy’ and ‘implementation’, but in most cases these matter less than having public officers who set out to do right for people, who are willing to try things out, who measure what matters, and are honest with themselves about what really works.