Take a BOW: smart software for robots

Robotics startup BOW’s name may seem quite evocative – ‘Bettering Our World’ – but it speaks to a broader mission of recognising existing issues within the robotics industry and seeking to address these issues through its robotic-agnostic software development kit (SDK).

What this means is that regardless of the robot or the operating system, using BOW’s SDK, developers are able to program software for it. In essence, what BOW is trying to achieve is similar to “what Android did for the smartphone, or what Microsoft did for personal computing in the 1980s,” said Nick Thompson, Co-Founder and CEO.

BOW was founded in 2020 as a spin-out from the University of Sheffield by Daniel Camilleri, Founder and CTO, and since its founding other experienced executives have come on board. Among its ranks is Thompson, whose background in software development can be traced back to the nineties when he started as a software developer and has been valuable to a startup utilising software to build robotic applications.

An overview of the technology

BOW’s robotic-agnostic SDK works by providing developers with a simulator in which they can choose the robot they’d like to program the software for, and test how it would perform in that same simulation.

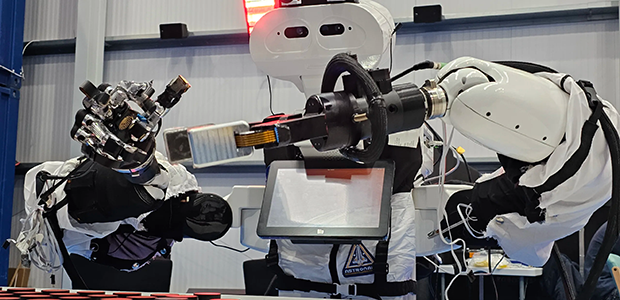

“An example might be a robot arm,” explained Thompson. “There’s a lot of technology in our platform where you can position the end of a robot arm, like the gripper, and program it to pick something up. You could try that on a robot arm and then buy it and install the software.”

The programming languages that can be run on it include Python, C#, .NET, Unity, and C++.

“It works on Windows, which is unusual in robotics,” Thompson added, “it works on Linux, and very shortly we’re launching the Mac Edition as well.”

The SDK is targeted at software developers who are accustomed to building websites and mobile apps using these programming languages and whose skills are transferable to building robotic applications.

Addressing interoperability

In equating the ease with which a mobile phone can be purchased and different apps can be installed on it, Thompson explained that BOW wanted to serve a similar purpose for robots.

“It shouldn’t be an issue which hardware manufacturer I buy the hardware from,” he stressed. “That’s an everyday thing for mobile phone users, but that doesn’t happen in robotics. You’ve got some manufacturers who are saying, ‘We’ve got a humanoid and it’s not programmable because we want to own that’ … You’ve got others that are saying robots are commoditised and can’t do anything you want them to do.”

BOW sits in the latter camp, as it’s looking to resolve this software interoperability among the various robots and form factors (such as robot arms, humanoids, and quadrupeds) that exist on the market today, as well as the number of roboticists capable of programming software. According to a number cited by Thompson, this number is finite: there are 100,000 roboticists in the world, compared with approximately 30 million software developers. To be able to allow these ready ranks of software developers to program for robotics would be a huge boon.

Another issue rests in how roboticists approach programming. Robots can be understood through the hardware – the physical robot – and the software, which effectively allows the robot to view and interact with objects as a human would. The software can be split into two sections: the control of the robot and the data gathering side, achieved through cameras and sensors, and the cognition side, where the data is interpreted and the robot makes informed decisions based on the data.

“It might be that you’ve got a robot that can intelligently see the world around it through LiDAR or cameras, and it’s making decisions on what to do next … we need to write the software to do that.

“That’s what the developers should be doing,” Thompson continued. “At the moment, roboticists are trying to do the whole stack, and that’s the problem. So we’re splitting it.”

All of these issues add up to the overall awareness that robotic applications are being hindered, and neat theoretical use cases from using a vacuum cleaner with robot arms to move things out of the way as it cleans, or robots for mission-based patrolling, is arguably being held back.

These examples provided come from applications that Thompson himself has seen people build using the BOW SDK.

“There is a lack of specific use cases for them because it’s difficult to write the software and get them moving,” said Thompson. “We’re bettering our world by empowering software developers to build any kind of software.”

In the coming months

BOW is continuing an age-old software development tradition of creating tools that make building software faster, easier, and better. Thompson listed AI tools as one example of how software development has evolved.

The closest competitor he could name to BOW, however, was the Robot Operating System (ROS). ROS are creating an open-source, agnostic platform for robotics targeted at academia and roboticists.

“They’re not really competitive,” he said. “They’re more of a collaborator. You could have a ROS-enabled robot and have BOW running on that as well. It’s all helpful.”

Since its establishment, BOW has experienced several milestones; in November 2024 it appointed Liz Upton, Co-Founder of Raspberry Pi, as the Chair of its board, and more recently, closed a £4 million seed funding round. Thompson joined in 2024.

In the coming months, Thompson said it hopes to relaunch the product and build a pathway to revenue.

“No software is ever finished,” he said. “That’s a fact … There’s no such thing as finished. We will continually evolve this software and add more features and more robots. That’s the main thing.”

This article originally appeared in the March/April 2025 issue of Startups Magazine. Click here to subscribe