Should startups focus on sales or building a brand? Part One

Over the past two decades, we have witnessed a drastic shift in how companies allocate marketing dollars and how they measure success of their marketing and advertising efforts. Google, Facebook, and Amazon (and recently TikTok) gobble up billions of ad dollars for their ‘performance ads’, ads that promise a click and immediate transaction that can be easily calculated, and performance immediately measured.

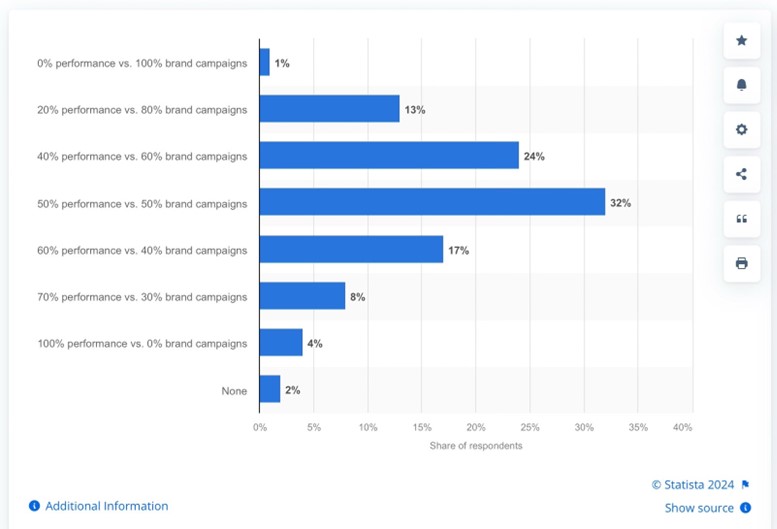

Many brands now spend a huge proportion of their marketing budget chasing these clicks, bidding for the lowest possible cost per acquisition. According to a 2019 Statista survey, 61% of advertisers responding allocate 50% or more on performance ads, and 4% spend exclusively on performance ads. I have seen studies, read articles, and had discussions with marketers suggesting the percentage of performance spend has skewed even higher in 2024.

The apparent goal of this spending shift is to short cut the process of brand building and generate faster revenue or profits by creating more immediate transactions. It’s reasonable that this performance ad percentage has moved even higher since the pandemic, when shoppers only had e-commerce at their disposal, and it appeared many marketers bought Facebook and Google ads during that time and went to the beach or binge-watched Netflix. While it’s easy to understand the temptation to allocate spend where it can be easily measured (the finance people love this approach), is it the most effective approach for a start-up, or should start-ups be more focused on building a brand asset from day one?

While tempting to opt for immediate sales, the approach may backfire

In the four decades I’ve been an entrepreneur, I have seen some massive changes in the marketing and advertising landscape. When I began my career in the mid-80s, new brands had a few media options at their disposal to tell their stories: network TV (usually too expensive for new companies), cable TV, radio, print, outdoor, direct mail, in-store displays, public relations, and event sponsorships. In the early 90s, the internet brought a new and affordable medium that offered great promise with regard to closing the loop between brand messaging and actual sales. In some people’s opinion, the holy grail of advertising had been found. The answer to John Wanamaker’s famous conundrum – “I know that 50% of my ad spend is wasted, I just don’t know which 50%” – was closer to being solved. Eureka!

I remember vividly when I was first introduced to the internet. I was running a company called Bates Promotion Group (part of the original Saatchi & Saatchi holding company and Bates Worldwide advertising network). I was sitting in my office in the Chrysler Building in the spring of 1994. Mark Morris, an old-school ad industry veteran and head of account services for our sister agency, Bates Worldwide, sent two people in their early 20’s (full disclosure: I was only 31 at the time) into my office to show me something he was excited about. Caroline Horner was a wide-eyed junior account person, full of energy for this new technology, the world wide web. Mike Golden was a matter-of-fact technology guy with an infectious grin (not sure the exact role he played at Bates at the time, but he briefly became our internet guy before leaving to start Organic Online, which he later sold for millions to Omnicom). Mark Morris had sent Caroline and Mike to me because he saw this new technology as a promotional medium, or even electronic direct mail, rather than a medium for brand advertising, and I ran the division that focused on what was then called alternative media (code in those days for everything not television, print and radio).

I was intrigued by what I saw that day, even though the technology was very rudimentary. There were only a few search engines (I remember using Alta Vista and Lycos), and the graphics capabilities were basic by today’s standards (think 1950’s cartoons), as was the interactivity (remember, we were less than a decade into the widespread use of email in 1994, and the best interactive device at the time was a landline telephone, so it was nothing like today). Making matters worse, computers did not have much bandwidth, so very few people could use much of the available technology (I remember paying a premium to install T1 lines in the office, not common at that time, so we could work faster), and brands were limited with how this new medium could possibly help their advertising efforts.

However, we found some pioneering clients. One, Yann DeRochefort of Perrier, was interested to see how we could use a website to promote the brand. So we made the first ever Perrier website, which was a simple series of pages promoting elements of their current marketing campaign (which featured art on Perrier bottles). There may have been a few clickable elements in our design, but it was basically a poorly animated ad on the world-wide web, created for what would seem now like a ridiculous six-figure fee for what the website actually could do, which was almost nothing. This was typical in the early days - while the internet promised the holy grail of instant consumer interactivity and purchases, and immediate access to a world-wide market, it was really just a screen with some information and images. It wasn’t until about 2000 when we started to see a glimpse of the reality we have online today.

Since that day in 1994, I have watched the pendulum swing, slowly at first and then quite quickly, from a world where most brands spent a majority of their budgets on carefully planned storytelling designed to create awareness and affinity for their products, to a world where more than half of budgets (and a much higher percentage for smaller, start-up brands) are spent on quickly developed, less thought-out (in some cases, it would seem not thought out at all) ideas designed to get immediate clicks and the all-important ROAS (return on ad spend).

The process for some brands at times appears to be ‘let’s try as many ideas as possible, regardless of brand relevance, and see what sticks and gets clicks.’ Unfortunately, this mindset is also creeping into non-perfomance advertising activities, where ideas that simply get attention may be favored over those that actually make sense (we all remember Bud Light’s recent debacle). As a result of all the short-term thinking used in performance ads, perhaps not enough young marketers are being trained how to properly build brands, instead learning only how to drive clicks and attention for immediate, measurable returns. If you are managing a start-up, beware of telling the WRONG story early in your development. Remember the old saying, “you never get a second chance to make a first impression.” That statement is especially true for start-ups launching new brands. Deliver the wrong message, and consumers will quickly write your new product off without giving it a moment’s thought. And they are not likely to pay attention the next time, either.

I understand the seduction of this quasi-scientific experimentation approach, especially to people trained in science or data (where many entrepreneurial marketers are born today), or math and finance (where numbers rule the day). While logic and data would say this approach should be preferred, and that getting clicks and sales is the ultimate goal of business, there is another side to this story. Brands are assets built by a combination of art, science and EMOTION. Building them requires the ability to foster and nurture relationships between people and things (inanimate goods and services) through a series of actions that are intentional, not accidental or incidental. The difficulty in doing this well, or even at all, explains why most brands fail, and why a few (the so-called super brands) dominate their categories.

What is a brand and why create them?

A brand is a symbol of trust. It’s a name or a mark that represents what can be expected from the brand (and product’s carrying the brand name) by consumers, now and in the future. Consistent delivery by the product is a vital brand characteristic. A brand is also a differentiating symbol that, like a person’s name, that declares “I am a unique product/service, better than all competing products/services like this.”

Nurtured effectively, brand’s become valuable assets that make up a large percentage of a company’s total value. Because of their unique appeal to consumers, which can border on fanaticism for successful brands, they command higher prices than mere commodity products that can be easily interchanged. Carefully managed brands create a moat of safety against competing products because consumers want to buy the real or original thing, or the one that is best according to their perception (and that of their friends and other influential people they trust and respect). As the famous saying goes, perception is reality, and brands are built on perception.

In 2023, the Coca-Cola trademark was valued at $106 billion dollars! This did not happen by accident, or by throwing ideas at the wall to see what would stick, or get clicks. The attention paid to detail in building this brand over a long period of time was so intense that the design brief for its iconic bottle dictated that the bottle should be “so distinct that it could be recognised by touch in the dark or when lying broken on the ground.” How many brands do you know today are willing and patient enough to put that kind of stake in the ground?

The peril of poorly managed brands is that they are vulnerable to an easy attack by well-funded competitors with similar, and perhaps even inferior, products. If Coca-Cola had not spent the time and money to create the powerhouse brand it is today, you might be ordering Amazon Cola today. But even the rapacious Amazon knows better than to waste its resources barking up that tree. There are many easier products to prey on, one’s that have not built powerful brands and have only been chasing clicks and grinning at short-term sales results. Too many have stopped smiling after being brought down to earth by the 800-pound master of click-induced disaster. Just look at Amazon’s success in competing with products initially launched on Amazon – this is what happens when a product puts too much weight on performance ads and does not spend enough time building a brand with fanatical appeal AND a protective moat. They are easily replaced. In a bricks-and-mortar comparison, supermarkets brands tried for years to aggressively compete with Coca-Cola with private label colas, using their distribution and shelf control. They eventually realised that consumers wanted the real thing and gave up. Coke (and Pepsi) brands were just too strong with consumers.

Brands matter because they create and add value. Sales are good, and essential to operate as a business. As a startup, sales can mean survival. But BRAND-driven sales are better and more profitable. They may take more investment and time to get, but the juice is worth the squeeze. Just as your body can’t build muscle without protein, brands can’t build value on performance ad offers alone. They must take into account the human element of decision making and the role human nature when it comes to creating relationships.

In Part 2 of this article, we will explore how brands actually grow (hint: you must make your brand relatable to consumers, so consumers will intensify their preference over time and experience with the brand).